Why Is the Art Market Hot if the Econkmy Is Bad?

A version of this story originally appeared in the fall 2019 artnet Intelligence Written report.

The date on the New York Times in your easily is September 21, 1989. Y'all're on the subway dwelling, trying to read the cover story most Mikhail Gorbachev purging the USSR'southward Politburo, simply Mayor Ed Koch'southward plan to air-condition every train in New York hasn't reached the one you lot're on, and the heat is oppressive. Besides, yous're too anxious that the big deal you're trying to shut for your auction house may simply blow upward in your face up.

There's a new collector in Tokyo you demand to call afterward this evening's episode of Cheers ends. The fax he sent you at the cease of his workday came through as nothing more than a smear of black ink, so information technology's still unclear if his financials really check out. He says he'due south in real estate (naturally), and the mode the Japanese marketplace has been climbing for the past few years, there's no telling how much he could spend in November if he'southward serious. A single Van Gogh almost hit $54 million less than ii years agone, and the Impressionist market has stayed then volcanic since so that yous're starting to dream the record could be broken again soon.

Problem is, you couldn't find the collector's card in your Rolodex today. Your assistant is driving to Florida, so you won't be able to ask where it might accept gone until she calls you from a cabin room to bank check in tomorrow morning. Too bad those new "mobile phones" Motorola just released toll $three,000. Then once again, holding a wireless electronic device upwardly to your ear all day probably gives you lot cancer or psychosis, so the whole product line might exist expressionless in a yr or ii.

Young buck Larry Gagosian cozying up to Leo Castelli in 1996. (Photo: Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images)

Speaking of psychosis, you lot wonder if Leo Castelli is losing his mind. At dejeuner today, you finally stopped by 65 Thompson Street in SoHo, where a few months back he started up a partnership with that 40-something LA shark Larry Gagosian. As if fighting with the other sale houses didn't make your life hard enough, Gagosian has been running effectually for the by few years acting similar dealers accept some kind of God-given right to compete in the resale market. What does he think, sale houses are going to commencement putting on exhibitions and offering works by living artists? Doesn't he understand there'south a particular mode of doing things in this business? Is the whole art globe every bit we know it breaking downwardly?

Fast-forward 30 years from this hypothetical day in the life and it's clear that, in a manner, the fine art world as information technology existed dorsum then really did break downward over the ensuing decades. That clubby handshake business where everybody knew your name has been replaced by a multibillion-dollar international industry.

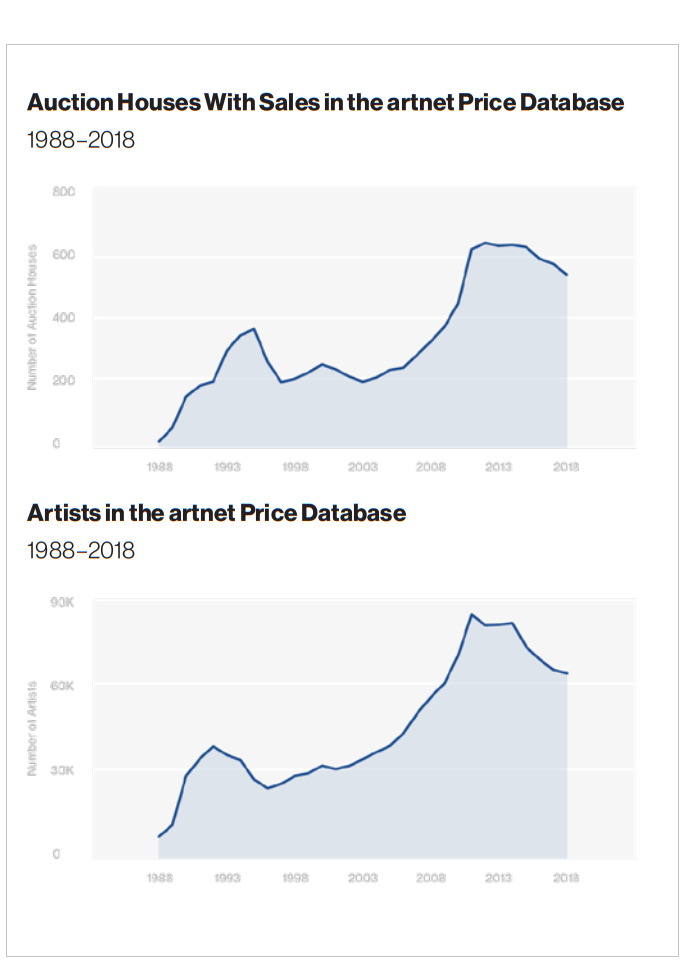

Today, that industry yet has plenty of growing upward to practice, but the refinement process has begun. Consider that, in 1988, the Artnet Toll Database tracked only 18 sale houses and well-nigh 8,300 artists. Over the next 24 years, those figures skyrocketed: By 2012, in that location were 632 auction houses and 90,275 artists. Simply, like whatever mature industry, it is now entering a period of consolidation after decades of expansion. Last twelvemonth, Artnet recorded simply 534 houses (a driblet of around 16 percent from the loftier-water mark) and 71,621 artists (downwards 25 percent from the peak).

Still, the scale and contours of today's art globe would have been largely inconceivable to dealers, auction-business firm professionals, and collectors 30 years ago. Tastes have changed; non-Western economies have emerged equally essential forces; and what was once a quaint cottage manufacture has get surprisingly corporate.

How was this transformation possible? Considering three supposed truisms well-nigh the art market place in the tardily 1980s have proved to be totally, completely wrong. Hither, we explore the art-world myths that the ascent of the art industry shattered.

Myth ane: Contemporary Art Volition Never Be Popular

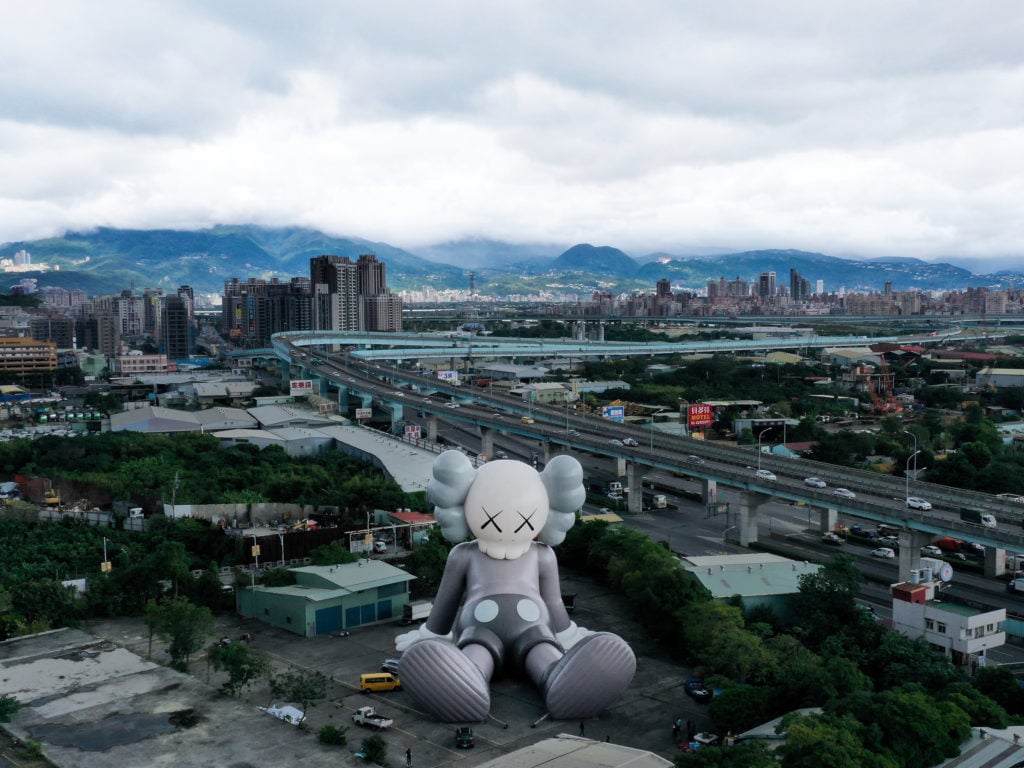

Information technology has been said that "we are what we repeatedly do." And based on the history of Artnet Price Database searches, nosotros take become an industry ravenous for artists who started out in graffiti, vinyl toys, and (peradventure staged) documentaries. The artists who saw the greatest increase in interested users over the past xv years include KAWS (#1), Mr. Brainwash (#6), and Banksy (#7).

The rise of street art would no dubiety exist jarring to the dealers and collectors who were battling over Van Goghs in the tardily 1980s—as would the realization that what is driving the market place is the ascent of young art in general. About of the artists occupying this list'due south upper reaches—40 of the top 50 names—were built-in in 1945 or subsequently.

"The attention contemporary art gets today is what we were always hoping for," says Thaddaeus Ropac, whose five international galleries grew from a single location in Salzburg opened in 1983. "It was once a minor group of followers—we were happy with whatever number of visitors we got; nosotros were happy about any pocket-sized auction. But expectations today are on a totally different level."

This trend toward the new is unmistakable in the data. For instance, of the 150 artists with the greatest increase in interested users since 2005, just i does not qualify as either postwar (which covers artists artists built-in between 1911 and 1944) or contemporary (artists born after 1945): the abstruse color theorist Josef Albers (1888–1976). And he ranks seventy-tertiary.

© Artnet Intelligence, 2019.

From today'southward vantage betoken, it seems almost unbelievable that an era existed when contemporary piece of work—which by its nature mirrors the issues and spirit of its age—did not bask such wide popularity. Only Allan Schwartzman, chairman of Sotheby's Fine Art Division, recalls that there was "no market place for contemporary art" as recently as the late 1970s.

That all changed in the big-money 1980s, a decade during which, he says, art began "being filtered through the eyes of dealers" who largely championed "brash, bold, invincible" works by the likes of Julian Schnabel, Anselm Kiefer, and Robert Longo. The stock marketplace crash of 1987 and the AIDS crisis threw a shroud over this Masters of the Universe mentality. The newly foreboding climate chimed with "a more introspective sensibility" shared past several of import young artists whose work explored themes of mortality, intimacy, imperfection, and transience. From Robert Gober and Marlene Dumas to Rirkrit Tiravanija and Elizabeth Peyton, these artists "became the disquisitional names in art, and often in collecting, in the decades that followed," says Schwartzman.

As the number of wealthy individuals effectually the world grew from the tardily '90s into the 2000s, demand for artworks as symbols of refinement and success drastically increased—and contemporary art had inherent advantages over older art among all merely the most moneyed of this dominant class. That's because, while the very acme of the market became increasingly sophisticated about which pieces across unlike genres were worth meaning price premiums, the rank-and-file rich gravitated to the next best and most available matter. And works by living (or recently dead) artists vastly outnumbered the classics.

From gallery dinners and studio visits to art-fair parties and biennials, the social incentives also heavily favored the contemporary, particularly as the amount of money flooding into the art business concern made these events more lavish and exclusive. This revenue boost translated into bigger budgets, greater appetite, and more robust marketing for successful galleries and artists.

Jay-Z and Marina Abramovic during the filming of Picasso Baby in 2013. Courtesy of Footstep.

Soon, this expansion became a virtuous cycle. The more contemporary fine art bubbled over into the celebrity and mass-civilisation spheres, the more global brands were peachy to partner with artists, and the more popular the artists became. Audiences can now encounter the piece of work of fine artists in Jay Z videos, on the comprehend of Vogue, on Louis Vuitton handbags and Nike sneakers, in tequila advertisement campaigns, and in a thousand other venues far more than visible than the traditional art context—and museums reap the benefits of this enlarged viewership.

Consider the fact that the Broad, the privately funded Los Angeles museum opened in 2015 by Eli and Edythe Broad, 2 of the most prominent collectors in the emerging class of contemporary mega-buyers, became 1 of the 15 near-attended American museums in its first year and has since grown its audience by 12 to 15 percent annually.

© Artnet Intelligence, 2019.

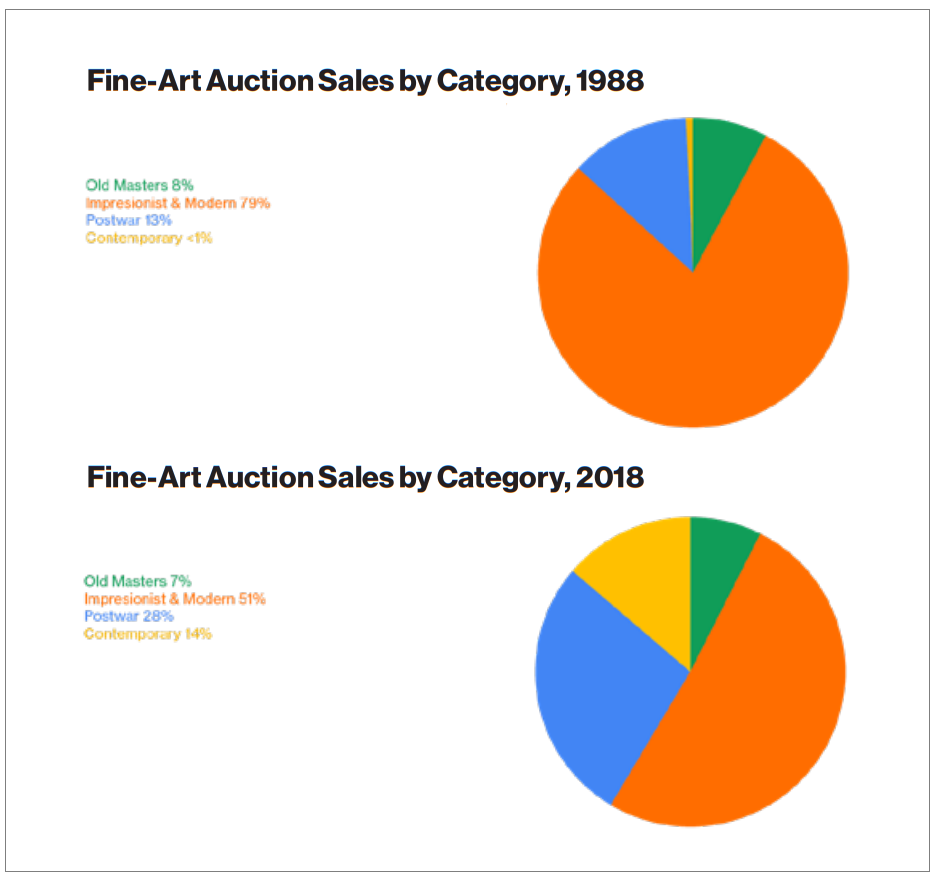

But does a huge gain in involvement in contemporary art correlate to a major rise in sales? Aggrandizement-adapted auction results over the past 30 years certainly say so. Artists born after 1945 have seized more auction market share than any other segment in the past three decades, going from just 0.8 percentage of total sales value in 1988 to thirteen.seven pct in 2018. That'southward a gain of 1,700 percent.

Of the remaining categories of fine art, but postwar increased its market share over this time frame, from 12.five percent in 1988 to 27.7 percent in 2018—a very healthy boost of about 120 percent, but an club of magnitude less than the game-irresolute growth of contemporary art.

Myth two: Sale Houses and Art Galleries Are Different Things

Unpacking how and why sales gravitated toward the new lays bare some of the most cardinal changes in the fine art world since the late '80s. One of the biggest is the breakdown of the traditional border between auction houses and galleries. This development, which is arguably still in its early stages, has washed much to transform the fine art business into a mature manufacture able to exploit the growing opportunities that lie before it.

© Artnet News Intelligence.

30 years ago, sale houses did not sell much gimmicky art, which was considered the domain of art dealers. "When I joined the business, there was a rule that you wouldn't offer an artwork past a living artist that wasn't at least ten years old, and so zero truly contemporary was offered in a postwar sale," recounts Phillips chairwoman Cheyenne Westphal, who began her sale career at Sotheby's in 1990. "That has inverse dramatically."

Among the biggest signs of this shift were the sales at Sotheby'due south of objects and ephemera from Damien Hirst's Pharmacy eating house in 2004 and the 2008 "Beautiful Inside My Head Forever" auction of Hirst that, Westphal recalls, "bypassed whatsoever gallery system and did something you would call 'straight to consumer,' which was definitely not a term used in the art world at the time."

Haunch of Venison, as seen from the street. Courtesy of Haunch of Venison.

The collapse of the distinction between auction houses and galleries occurred "pace by step," according to Ropac. He recalls Sotheby's 1996 conquering of André Emmerich Gallery, then primarily known for representing American color-field painters such as Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland, equally an early milestone in a "tiresome process" through which the sale houses "tried to empathise how they could get the all-time out of contemporary art." Christie'southward followed arrange in 2007 by acquiring the international contemporary gallery Haunch of Venison, which then handled the likes of Richard Long, Bill Viola, and Rachel Whiteread.

The major houses eventually realized that running galleries that represented living artists was, in Ropac'due south words, "a step too far, and stepped dorsum" to, at most, operating exhibition spaces focused on private sales. Simply even this development was a meaningful one, and their consignments of contemporary works less than a decade old gradually moved from day-sale experiments to evening-sale fixtures over the past 10 years, at to the lowest degree in the United States.

Auction house employees human being the phones during the "Beautiful Inside My Head Forever" sale at Sotheby's, September fifteen, 2008. (Photo by Daniel Berehulak/Getty Images)

Dealers have been equally responsible for redrawing the art market's borders. From Lucy Mitchell-Innes and David Nash, who exited Sotheby's in the mid-'90s, to Brett Gorvy, who departed Christie's in 2016, major auction-house staffers have proved increasingly unafraid to pin to the gallery sector, where new work from the studio is, in many cases, offered alongside secondary-market fabric premium plenty to lead an evening auction.

This exploding distribution mechanism for contemporary piece of work powered upwards the sector in a way that no competing category could match. It is no coincidence that the menstruation during which the contemporary category fabricated its greatest gain in the auction market—between 2004 (when gimmicky deemed for 5.9 percent of all sales) and 2014 (14.ix percent)—maps nearly exactly onto the i in which the number of worldwide art fairs ballooned (from 68 in 2005 to more than 220 by 2015).

And so why is this increasing overlap betwixt auction houses and galleries significant? Because each sector lacks what the other offers. Auction houses have corporate structures that allow them to calibration upwardly their operations on a global playing field and pursue long-term strategies despite changes in CEOs or ownership, but they lack access to fresh-to-market inventory. Galleries, on the other hand, have direct access to artistic production, but they are oft passion-driven businesses operated by a charismatic founder (or founders) whose unique gifts and relationships cannot be hands transferred to successors. Combine the two, and you accept something approaching the kind of vertically integrated corporate construction that has enabled companies in other industries to thrive in a global marketplace.

The facade of Gagosian, courtesy of Shutterstock.

We're non at that place yet, to be sure, but this increasing hybridization shows no sign of slowing down. This spring, Gagosian appear the appointment of gallery veteran Andrew Fabricant to the newly created position of chief operating officer, the establishment of a 24-member informational board of top salespeople, and, perhaps most notably, the creation of a new, separate business called Gagosian Art Advisory, LLC, led by Christie's veteran Laura Paulson.

The move echoed the acquisition by Sotheby'due south, three years earlier, of the art advisory firm Art Agency, Partners. For both high-end galleries and sale houses, information technology seems, the goal is to transform into 360-caste art-service juggernauts capable of handling a client's every demand, from individual buying and selling to advising and estate planning to collections management and logistics. The race is on to see who will be all-time able to capitalize on the opportunities created by the growing—and increasingly global—market, ultimately becoming the LVMH of art.

Myth iii: There Is No Such Affair equally Global Taste

Information technology can be like shooting fish in a barrel to forget how far the art marketplace has come in Asia, and how fast. Patti Wong says that when she was appointed chairman of Sotheby's Hong Kong in 2004, the metropolis was even so viewed as a "regional hub" whose business relied on "Chinese collectors buying Chinese things."

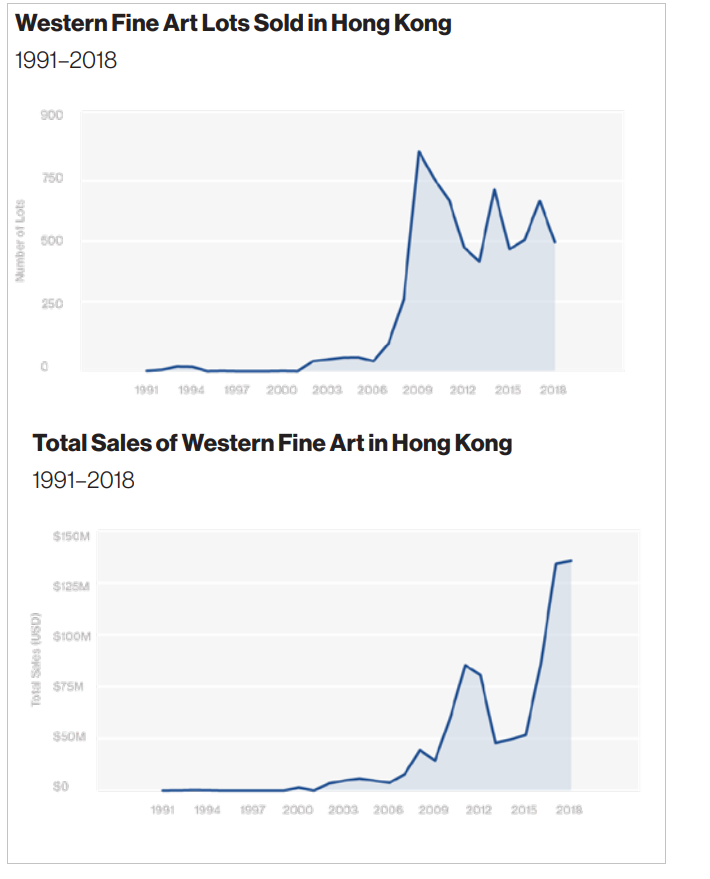

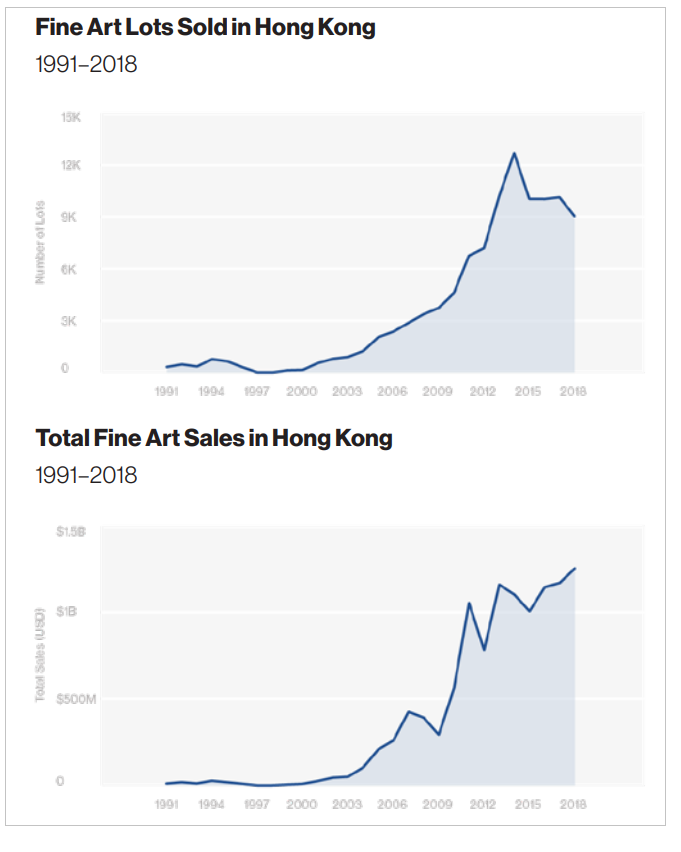

Indeed, from 1991 (when Artnet's records for Hong Kong begin) to 2004, a grand total of simply 124 works past Western artists sold at sale in the urban center, with a combined value of roughly $12.i million. Fast-forward to 2018, and 498 Western works collectively brought in $132.7 million—about 1,100 per centum more than in one year lonely than Western art fabricated in that first 13-year stretch.

Sotheby'southward staff take telephone bids during an auction at Sotheby's in Hong Kong on April 3, 2018. Photo: Isaac Lawrence/AFP/Getty Images.

Only as telling, Wong contends that a "key message of the last 10 years has been the Asian buying power exterior of Asia," with sales in New York, London, and other Western markets being increasingly propelled by E Asian clients.

In this respect, fine art is aligned with other 21st-century businesses. The globe'due south major commercial and cultural economies are now intertwined to an unprecedented degree. It seems completely intuitive, for instance, that Marvel's Avengers: Endgame grossed $178 million at the mainland Chinese box role over Labor Day weekend, or that information technology is as easy to find a Chanel shop in Seoul equally in Paris or New York.

© Artnet Intelligence, 2019.

Withal baddest Western art did not become blue-scrap global art until the 2010s. It isn't but that the preceding decades saw vanishingly few works by non-Asian artists come to sale in Hong Kong. The Western artists with strong presences in East asia during this before era tended to be regional sensations with little to no force nether the gavel in other fine art-market hubs. In fact, fifty-fifty though he was Belgian by birth and ethnicity, one of these early top-sellers, the Modernist painter Adrien Jean Le Mayeur de Merprès, is usually included in Sotheby's sales of Southeast Asian fine art today.

Looking strictly at paintings, the height-selling non-Asian talent in Hong Kong during the 1990s was British artist George Chinnery, whose renditions of Chinese subjects and scenes clustered most $124,500 at auction. The 2 decades since and so accept been led by Le Mayeur, who spent much of his career in Indonesia (and whose regional fame culminated with a museum in his honor in Bali). His paintings brought close to $twenty.3 meg in the 2000s, and and have earned more than $43.1 meg to appointment in the 2010s.

Le Mayeur bated, the sales rankings will look much more familiar to the average Westerner since 2010, subsequently which indicate the internet, the identical international excursion traveled by socioeconomic elites, and other factors seem to have carried blue-chip artistic taste by an inflection point. The other pinnacle-sellers at Hong Kong auctions to engagement this decade are KAWS (well-nigh $37 million), Jean-Michel Basquiat (about $30 million), and Gerhard Richter (nearly $25 1000000).

Art Basel Hong Kong. Courtesy Art Basel.

Eastward Asian collectors oasis't just become more than international in an astonishingly short period of time. They have also become dramatically more discerning. Only a few years ago, Allan Schwartzman says, the predilection for "buying names rather than works" made the region's buyers vulnerable to "various people in the market who took advantage [of them] to sell inferior works at healthy prices." Those days are gone. According to Wong, "Asians rely on data," typically researching not just previous sales prices but likewise how those prices landed relative to presale estimates so that they can make shrewd decisions.

The consequence? Hong Kong is apace approaching cost parity with London and New York, if it is not already there. Equally show, Wong points to the results for Andy Warhol'due south Mao (1973), i of the marquee lots in Sotheby's Hong Kong'southward Modern and gimmicky evening auction in April 2017, which included Western artworks for the first time. The peppery cerise sheet sold for the equivalent of $12.half dozen meg with premium—identical, in terms of US dollars, to the £seven.vi million it brought at Sotheby's London 3 years earlier and a gain of £2.4 1000000 if the pound sterling's drop over that period is taken into account.

This accelerated learning curve has equipped the art market place every bit a whole to expand quickly and aggressively throughout East Asia. The inauguration of Art Basel Hong Kong in 2013 ushered in a new era for the territory'southward relationship to Western galleries. Although Step recently appear information technology would shut its Beijing space, the globe-spanning gallery continues operating in (currently protest-ridden) Hong Kong, which also plays host to such heavyweights as Gagosian, David Zwirner, Hauser & Wirth, and Lévy Gorvy. Other high-tier galleries accept fix permanent spaces elsewhere in the region: Perrotin and Lehmann Maupin in Seoul; Sean Kelly in Taiwan; Blum & Poe in Tokyo.

KAWS, Holiday (2019). Photo: courtesy of AllRightsReserved.

This evolution has been largely driven by E Asia'south showtime-generation inheritors of mega-wealth. A big proportion of this demographic grew upward in families that collected in more than traditional categories, such as regional antiquities or Chinese ink paintings, and were educated (and culturally embedded) in the West during some of their formative years.

"It'due south quite regular that nosotros have a collector in his late 20s or early 30s buying seriously at sale—and not just ane or two, only in volume," says Westphal. "It's a generation of collectors very used to absorbing information, very keen on finding out what is going on and what is going to be the adjacent big matter, and driving that, as well."

© Artnet Intelligence, 2019.

Having ii generations of collectors with roots in E Asia has made a colossal difference for the Hong Kong auction market. In 1991, Hong Kong houses in the Price Database combined to sell 313 fine artworks (past both Asian and not-Asian artists) for $x.9 million. In 2018, a total of 9,017 works inverse hands to generate nigh $1.4 billion in sales, a 234-fold increment in 27 years.

Wong says that agreement the data-driven mind-fix of E Asian collectors has allowed Sotheby's to, in her words, movement beyond "what people expected: the Warhol Mao, [Yoshitoma] Nara, [Yayoi] Kusama" and begin offering loftier-quality works by artists with solid market profiles merely no sustained prior presence in Asia. Final Apr, for example, Sotheby's Hong Kong ready new world records for both Ethiopian-born, New York-based painter Julie Mehretu and New York-based awareness KAWS.

This is why Wong says Asian collectors "no longer just follow the data but are function of making the data" that charts the global market's path—a development many would have considered unthinkable 30 years ago. So the adjacent time you hear a colleague or client gripe that the art market is doomed to proceed repeating the same mistakes, feel free to remind them that an awful lot tends to alter in three decades.

A version of this story originally appeared in the fall 2019 artnet Intelligence Report. To download the full written report, which has juicy details on the most bankable artists, a survey of what top collectors are ownership and why, and a deep dive into the market for African gimmicky art, click here.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Desire to stay alee of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to go the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive disquisitional takes that drive the conversation forwards.

Source: https://news.artnet.com/market/how-the-art-world-became-the-art-industry-1710228

0 Response to "Why Is the Art Market Hot if the Econkmy Is Bad?"

Post a Comment